What is Tree Coppicing?

- By Fox Tree Services

- •

- 23 Apr, 2018

Coppicing has been traced back to Neolithic times by archaeologists who have excavated wooden tracks over boggy ground made entirely of coppiced material.

There are written records, going back to at least 1251, which describe the value and type of material cut for woods in East Anglia. Coppicing can provide a constant supply of material for a wide variety of uses. The material is of a size which is easily handled. This was very important before machinery was developed for cutting and transporting large timber, when anything more than 20 miles from a large river could only be used locally. Through the 18th and 19th centuries, coppiced woodlands provided industrial charcoal for the smelting of iron, and bark from which tanning liquors were prepared.

However, by the mid-twentieth century coppicing was in rapid decline and many coppice woods were replanted with conifers, or simply neglected.

Physiology of Tree Coppicing in Cardiff

Coppicing occurs when a tree is felled and sprouts arise from the cut stump (known as a stool). This process can be carried out over and over again and is sustainable over several hundred years at least, the stool getting ever larger in diameter. The shoots arise from dormant buds on the side of the stool or from adventitious buds developing in the cambial layer below the bark. Root buds can produce coppice shoots when close to the stump, especially in birch and hazel. The development of the buds is initiated by a change in plant hormone levels following removal of the crown or stem.

Species and growth

All broadleaves coppice but some are stronger than others. The strongest are ash, hazel, oak, sweet chestnut and lime whilst the weakest include beech, wild cherry and poplar. Most conifers do not coppice.

The number of shoots per stool depends on the species, its age and size. A large number emerge in the first year – up to 150 in some cases, but these quickly die off in following years as self thinning takes place. By mid rotation 5-15 are left. The final number depends on the rotation length and species. Sweet chestnut coppice cut in its 16th year has about 5,000 stems/ha.

Oak, hazel and lime commonly grow a metre in their first year; ash and willow can grow much more and in the second year growth is generally greater. From the third year, growth slows dramatically.

Organisation and Systems of Working

Coppice is normally divided into coupes (otherwise known as a fell, a cant, a hagg, or more simply a compartment). If cutting neglected coppice, it is usual to cut the most neglected areas first, but if usable material is required straight away, some better coppice will need to be cut as well.

As a rule of thumb, coupes should be at least 0.5 ha. However, under the UKWAS certification standard no more than 10% of semi-natural woodlands over 10 ha in size should be felled in any 5-year period. Large coupes have the advantage of deterring deer from entering.

There are two systems – coppice and coppice with standards. The former has no standard or maiden trees (i.e. no trees which are not coppiced). The coppice with standards system is much more common in Cumbria. Oak normally makes up the standard trees but they could consist of ash or, less commonly, birch. Standards should be retained at a density of about 30-100 per ha (a 10-18m spacing), and should consist of a variety of age ranges. Try to leave a few of the very oldest trees to grow on to become veteran trees.

Up to 40% of the canopy can be occupied by standards. When coppicing, look out for seedlings to protect and allow to grow on to form standards. Too many standards retained will result in poor coppice regrowth due to insufficient light reaching the ground.

Coppicing Technique

A sloping cut is traditional as it was thought to shed water and prevent fungal decay. However, there is no evidence that a sloping cut minimises fungal attack.

A low cut maximises the yield and encourages shoots to develop their own roots; it is also safer to work when stumps are cut low. The bark below the cut should not be damaged.

Work traditionally takes place during the winter – October to the end of March. There is no silvicultural reason for this but coppice which is cut during July, August and September will produce shoots which are not frost hardy. Coppicing during the spring will disturb nesting and trample the ground flora. Coppice material cut in the winter works better and lasts longer than that cut when the sap levels are higher.

Protection of Coppice

In Cumbria, especially in the south of the county, the deer population is usually too high to risk coppicing without suitable protection from browsing. The protection can take several forms:

- Exclude all livestock from the wood

- Stacking brash over stumps works where deer pressure is low, but is generally not effective

- Erect a brash deer barrier if manpower, materials and time allow – this can be effective for long enough for the regrowth to get away

- Erect deer fencing if the site makes this practicable and expense allows

- Erect individual tree shelters over regeneration or rabbit net protection around coppice stools if only protecting a few. Small circular fences of chestnut paling are thought to keep deer out (no more than 20m across). This type of fencing need only be temporary and can be used several times

- Electric fencing is quite effective but requires regular maintenance

- Control deer if numbers are high; professional help must be sought for culling

- Repellents work for a short time but require regular replacement as high rainfall washes away the active ingredient

More Post From Our Blog

As qualified Trees surgeons, we have been carrying out tree felling in Cardiff and throughout South Wales for many years. Felling Trees safely requires us to survey the site and establish the best method to fell the tree and avoid damage to the surrounding areas. We are happy to offer our Tree Felling site surveys for free to all our customers, along with any appropriate advice.

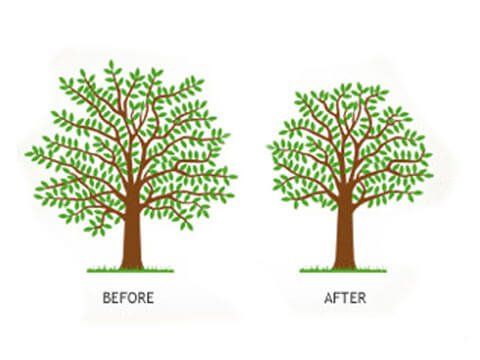

Pruning a tree is removing specific branches or stems to benefit the whole tree.